I’ve got two books to share! The first is We Need New Names, a novel by NoViolet Bulawayo. You should read it, if not for anything else, for the author’s arresting name! But, seriously, it’s a great story on migration and the different levels of displacement that attend to it when economic and racial pressures are applied. The young and sassy first person narrator Darling will reward you with shock, amusement, and much to think about for choosing to hang out with her this summer. If you are an English Senior, Bulawayo is also on the reading list for my section of the Senior Seminar this fall.

The other novel is Bernardine Evaristo’s The Emperor’s Babe. I haven’t read it yet, but the blurb is intriguing. Having read Evaristo’s earlier work, Lara, a semi-autobiographical verse novel that deliciously presents the myriad diasporic roots of Evaristo, reaching to Ireland, Germany, Nigeria, and Brazil, I am excited to read The Emperor’s Babe, which is also in verse form. But this is no turgid verse. It flows. The Emperor’s Babe is set in AD 211 London (or, Londinium as the Romans called it) and features Zuleika, the daughter of Sudanese immigrants who marries a Roman merchant. Evaristo likes taking poetic risks in language and I look forward to reading about romance and power play in third century London. By the way, Evaristo will be here at Villanova in spring 2016 as keynote speaker at the Cultural Studies Association conference. Not a bad idea to read one of her novels before she arrives.

MICHAEL BERTHOLD

This summer I plan to read through the Library of America’s collection American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s. As Junot Díaz says, “These novels testify to the extraordinary range, profound intelligence, and indefatigable weirdness of ‘50s American science fiction. A must-have for anyone interested in one of the most vital periods of our literature and for anyone who wants a wild wild tumble down the rabbit hole.”

CHARLES CHERRY

For a break from literature, I recommend Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997), a readable Pulitzer-Prize nonfiction winner. Many years ago, a New Guinean asked Diamond “why white people developed so much cargo [steel tools and other products of civilization] while we black people had little?” It took Diamond 25 years to answer that question. As Bill Gates notes: “this book lays a foundation for understanding human history.”

ALICE DAILEY

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day (1989). This is an exquisitely—even perfectly—crafted novel. The story is told as a series of post-World War II diary entries by an English butler, Mr. Stevens, who reflects on a career of dutiful service to his aristocratic employer even when it became clear that Lord Darlington was abetting the Nazis. The novel is a poignant, elegant, and subtle study of how moral will and personal fulfillment are effaced by the constraints of duty.

Joan Didion, Play It As It Lays (1970). This novel of Los Angeles makes me homesick and heartsick. It captures the rhythm and industrial beauty of the LA freeway system and offers an uncompromising depiction of the existential vacancy of Hollywood values: youth, beauty, celebrity, surface. In Didion’s long, distinguished career, Play It As It Lays remains a standout.

TRAVIS FOSTER

Sarah Orne Jewett, The Country of the Pointed Firs. The narrator of this slim novel, a writer, travels from Boston to coastal Maine for a summer of uninterrupted work. What she finds, however, is a concentrated lesson in the stages of friendship across difference: from the uneasy hesitations of initial meeting to the gradual accumulation of shared knowledge.

Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric. We’re maybe used to novels and even poems capturing something exceptional and, for that reason, noteworthy. In this book length poem about being black in a white supremacist nation, Rankine makes the mundane noteworthy. If you’ve read Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” you’ll recognize the epic scale Rankine locates in everyday occurrences, where casual gestures and offhand remarks recall hundreds of years of history and the clash of competing hierarchies.

Tana French, The Secret Place. French writes smart murder mysteries set in contemporary Ireland. I love them all. This one, her most recent, deals with a murder on the grounds of a girls’ boarding school. The chapters oscillate between the procedural perspective of the adult police and the meandering perspective of teenagers, a structure that allows it to highlight adolescence in all its unknown and terrifying in-betweenness.

Adam Phillips, On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Unexamined Life. One essay here begins with Phillips, a practicing psychotherapist, asking his patient, an anxious ten-year-old boy, to define “worries.” The boy thinks for a bit and then responds: “Worries are farts that don’t come out.” For most of you, that will be all the endorsement this volume needs. For the rest, let me add that Phillips is an enviably beautiful writer who will leave you smarter, more self-aware, and maybe even happier than you were before.

HEATHER HICKS

The Age of Miracles, by Karen Thompson Walker. It is a moving story of a young girl coming of age in a near future in which the Earth’s rotation is gradually slowing--a phenomenon that is wreaking physical and social havoc across the globe.

KAMRAN JAVADIZADEH

I seem to be in the habit of recommending books that are about poetry, or that are almost poetry, but that achieve this while remaining stubbornly free of line breaks. Here are two more for this summer, one short (that I’ve already read) and one long (that I’m reading right now):

1. 10:04, by Ben Lerner. This novel (by a poet) is set in New York City and bookended by two hurricanes, Irene and Sandy. It’s a slim book--quiet, ruminative--and reads like a dream. What’s it about? Too many things to name, but, chiefly, the porous line between life and art. Plus the best use (ok, the only use) of the film Back to the Future in any novel I’ve ever read!

2. James Merrill: Life and Art, by Langdon Hammer. Full disclosure: the author of this book, a biography of the poet James Merrill, was my dissertation adviser. Merrill was a fascinating figure, gifted beyond belief, and fully committed to a life in the service of art. And this biography again and again rises to the task of making its subject come alive, without sacrificing any of the subtlety of his art. I’m far from impartial, but totally taken by this book.

JAMES KIRSCHKE

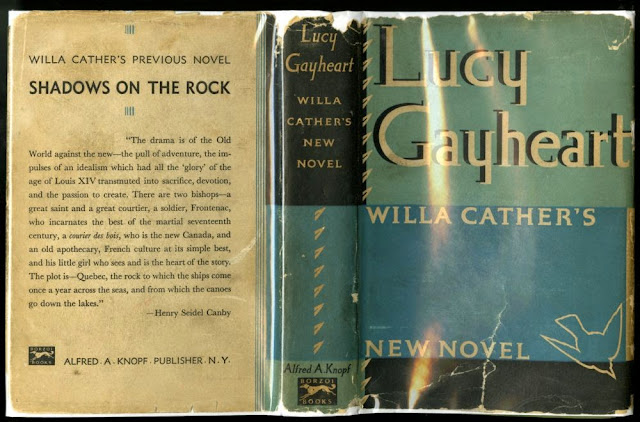

Lucy Gayheart, by Willa Cather. This short novel is extremely well written. The plot is nicely constructed. The language, as almost always with Cather, is a perfect fit. And the ending is extremely powerful. A moving love story.

JOSEPH LENNON

I’d like to suggest the novels of Glenn Patterson, who will be our Heimbold Chair for 2016. He is a Belfast novelist, and I loved Lapsed Protestant and The Mill for Grinding Old People Young, which was selected as the One Book, One City for Belfast in 2012.

CRYSTAL LUCKY

I’ve got God Help the Child on my bedside table, waiting. Nothing to say but, ‘It’s Morrison!’

JEAN LUTES

First on my summer reading list is Zia Haider Rahman’s In the Light of What We Know (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2014), because it sounds big in the best possible way: epic, global, provocative. Its story roams from Kabul to London, New York, Islamabad, Oxford, and Princeton, and I’ve heard that it considers, in one way or another, many of the key challenges of our contemporary moment in history. I’m curious.

As a teacher of the modern American novel, my summer pick is The Professor’s House (1925) by Willa Cather. It’s complex, ambitious, and atmospheric. Although it does feature a middle-aged college professor, at the novel’s center is the grand story of a young adventurer who stumbles upon the remnants of an ancient civilization in the Southwest.

ROBERT O’NEIL

Redeployment by Phil Klay recently won the National Book Award. This collection of short stories highlights the brutal nature of war in Iraq and the haunting memories that follow soldiers home. By showing both the battle and home-front, Klay provides readers with a searing and unflinching look into the Iraq War that will ultimately change one’s perspective on soldiers and war as a whole. Excellent read!

MEGAN QUIGLEY

I have three books waiting to go for summer. First, My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgaard. I’m desperate to start this book. The New York Times Magazine’s “Travels Through North America” can give you a sneak peak: click here. I’ve already started and am enjoying Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See and since it just won the Pulitzer, I better finish and see why! Finally, I’ve been sucked in by the hype surrounding the reclusive Elena Ferrante and her trilogy, starting with My Brilliant Friend. I can’t wait to see what the excitement is about!

EVAN RADCLIFFE

I’m a fan of the archetypal film noir The Maltese Falcon (1941) starring Humphrey Bogart as the detective Sam Spade (as well as of “Tequila Mockingbird,” the episode of the TV show “Get Smart” that parodied it). But I’ve never read the original 1929 novel by Dashiell Hammett, which is a classic of noir crime fiction and the original “California noir” novel. I’m reading it this summer as a prelude to next summer, when Alan Drew’s own California noir novel, Santa Ana, will be published.

LAUREN SHOHET

Orpheus Lost, by Janette Turner Hospital, adapts elements of the Orpheus legend in this engaging contemporary novel that takes its characters through the long-lived consequences of wars past and present.

Martin Blaser’s Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics is Fueling our Modern Plagues is as interesting for changing how we think about boundaries of bodies, of selves and others, as it is for its pragmatic prescriptions.